- Home

- Virginia Moffatt

The Wave Page 2

The Wave Read online

Page 2

Yan

Poppy … Poppy … Poppy … A name to march by. A vision of pale beauty on Facebook – slim hips, round breasts, long black hair - that is going a long way to helping me fight off the fear. It’s a fantasy I know, but given I’ve had the shockingly awful misfortune to be trapped here by the floods, I deserve a little luck, don’t I? Poppy … Poppy … Poppy … I walk through the shrubland to the beat of such thoughts. There’s a breeze up, but the sun is strong, and with a tent and food supplies on my back, the journey is tougher than I’d expected. I haven’t been this way for ages, and have forgotten how the land rises and falls, the bushes overhang, their roots throwing obstacles in my path. I stumble frequently. Today is made even worse by the waterlogged soil, which has created bog after bog for me to navigate. Normally the sight of the sea ahead – greeny-blue water glinting in the sunshine – would be enough to motivate me, but today it has lost its allure. It’s not just the thought of the destructive powers that will be unleashed tomorrow – I am thirsty, sweating; my legs ache, my boots are clogged with mud. I can’t help feeling that by the time I arrive at Dowetha I’ll be too tired to appreciate it.

At the stile onto the cliff path, I stop for a break, relieved to remove my burdensome rucksack and hurl it to the ground. I find a bottle of water and a bar of chocolate, plonk myself on my coat to protect me from the damp earth. I sit with my back against the wall, gazing back at the cow field I have just crossed and the standing stones in the distance. I’m hoping that by not looking at the sea, I can quell the panic, and pretend for a short while at least this is an ordinary hike, on an ordinary day, and nothing much is about to happen. I fail miserably. As soon as I stop, the full force of the last few hours sweeps over me like a tidal wave. My mind races through the events of the day, over and over again, leaving me no room to escape …

The news trickled out slowly at first. A twitter rumour followed by a rash of speculation on Facebook. Followed by a breaking news line on the BBC. By the time the first full article was up, their website crashed. Last time that happened was 9/11. Remember that? I was sitting at a computer at York, horrified by the suffering of people thousands of miles away. Today, as my screen filled up with a dizzying array of facts and figures, images, analysis, infographics, it dawned on me that this time the rest of the world would be the appalled bystanders, while I was here, right in the thick of one of the danger zones. And being on peninsula meant this particular danger zone would be more dangerous than most. I’m a statistician; it didn’t take long to make the calculation, to realize there was no hope of getting out of here alive. They were too many people, trying to leave by too narrow an exit. We didn’t have a chance. With the whole of the South East and Welsh coastlines expecting a battering, the government made it clear evacuation efforts would have to be focussed further north. There would be no use relying on the Dunkirk spirit to come to our aid. It’s not that people wouldn’t want to help, but anyone with a boat would be too busy getting themselves to safety, they wouldn’t have time to come down here and rescue us. There was some talk about organising plans, but most commentators agreed that there weren’t enough airstrips, and with the airlines arguing about airspace, the unions about staffing, and the Transport Secretary being too paralysed with doubt or fear to intervene, the wrangling got nowhere. It was clear to me we were on our own. There would be no way out.

I’m not sure how long I sat at my desk, considering my options. Should I cadge a lift from James in the vain hope that we could outrun the water? Hide under the duvet, with a bottle of whisky for company? Pills before bed, so I’d never wake up? None seemed appealing. It was only when I turned to Facebook that I found what seemed to me the obvious solution. The minute I read Poppy’s post, my mind was made up. Making the most of the time left sounded better than sitting in traffic or drinking myself into a stupor. And she was hot, the kind of woman I wouldn’t normally have a chance with. But in these circumstances? Anything might happen. So I gathered my belongings together, swimming trunks, warm clothes for the night-time, kagoul just in case, camping equipment, sleeping bag, tent, food and threw them in a backpack, and because I hate leaving a book unfinished, my partly-read copy of The Humans.

I was just emptying the fridge when there was a knock at the door. It was James, bag over his shoulder, keys in hand, road map at the ready. Oh, James. Ever the optimist. I tried to explain to him he was wasting his time but he wasn’t having any of it. He was desperate to persuade me to join him but I was equally adamant. Story of our friendship. Him half-full, me half-empty. Always leads to arguments in the pub and then days of mutual sulks till one or other of us tries to put it right. Today we took great pains not to go into our usual combative mode. When it was clear we couldn’t agree, we had a rather awkward goodbye on the doorstep and went our separate ways. It was so odd, that goodbye on the doorstep. Five years of propping up the bar, putting the world to rights, and now we’ll never see each other again …

… Never see each other again. The reality of that hits me like a wave of cold water. I managed to keep the dread at bay while I was walking, but now I’ve stopped for a bit, it is rising in my stomach again. I push it back down again as I get to my feet. I should keep moving, live moment, by moment. There is simply no point thinking about the future I don’t have. It doesn’t change anything. I hoist my pack back on my shoulders. The straps chafe; it feels heavier than before, but the rest and food has done me good. As I walk, my thoughts return to Poppy; I imagine her falling off the board, enabling me to come to her rescue. In her gratitude she opens up her wetsuit, and lets me rub my face in her breasts, and more besides …

Poppy … Poppy … Poppy … I walk to the beat of her name, thinking only of the ground in front of me, till I reach Dowetha. I dump my luggage at the clubhouse where I keep my surfing gear. I grab a wetsuit, and force my thighs through the constrictive material. Jeez, I’ve got fat. Working from home has confined me too my desk for too long. I catch a glimpse of myself in the mirror, wincing at the beer belly that indicates too many nights in the pub, too few in the water. God, I need to lose weight, an absurd and pointless anxiety now. I pick up my board and leave my gear behind. There is no need to lock the doors behind me – who will come here today but me?

As I turn towards the slope, it suddenly occurs to me that the message was fake, that I have turned up here full of ridiculous hopes that are about to be dashed. That all I’ve done is tire myself out with a long walk to reach a deserted beach and the prospects of facing my death alone. It is a relief to reach the top of the slope and see signs of her presence. A small blue tent pitched above the high tide mark, towels and a blanket spread out beside it. And there she is in the water: a slim figure, striding the waves till they crash on the shore. It is all the signal I need to run down to the water’s edge, ploughing through the waves with my board. I am careful not to come too close, I don’t want to crowd her. She is so focussed, she doesn’t notice me at first; it is not until I reach the surf zone that she acknowledges me with a wave and a smile. What a smile. It drives away every fear. I no longer care about anything other than the bliss of surfing alongside her. Waiting in unison for the swell, positioning the board, crouching, standing, riding the wave, till it takes us back to the beach. Then striking back out to sea for more. Again and again and again. We do not speak, we do not need words, already we are intimate. I could stay like this for ever.

That’s until the cold begins to seep through my wetsuit as the waves begin to strengthen in intensity. Ploughing back to the breaker zone begins to be an effort. Pride won’t let me stop till she does, and I am grateful when, at last, she shouts this should be the last one. I ready myself for the coming wave, rising at its approach, and then … disaster. The surf is stronger than I anticipated, I turn too sharply and slip off the board, my foot tangling in the rope. Suddenly, I am dragged under the water, eyes stinging with the salt, a rush of blue, green and yellow, a deafening gurgle of sea pounding my ears. I try to force myself u

pwards, emerging to gasp a breath before another wave knocks me down again. My lungs begin to hurt with the pressure, my eyes to tingle, my head to pound, as I flail up and down through the foam. Fuck, this is what is like to drown. As I slide down again, it crosses my mind that I might as well let it happen now. If I survive this, I am only delaying the inevitable. Why bother fighting it for the sake of a few more hours? But even as I have the thought, something inside refuses to give in to it. I push myself up through the water, and suddenly there she is. Her arms are round me pulling me through the waves. It wasn’t quite the way I planned it, but I love this sensation, lying back safe, cradled, as she transports me to my board, pushes me up, and helps me get back to the shore.

Once out of the water, and after we have disentangled the rope, I am able to sit back and catch my breath. I rub my ankle, red from the pressure of the rope, and thank her. ‘Thought I was going to drown for a minute …’ I grin as the thought occurs to me, ‘Ironic, considering.’ She grins back. When we introduce ourselves and I explain her Facebook post brought me, her smile is even warmer; I melt. I can’t stop myself from giving her a dopy smile in return. Luckily she decides she needs to change, giving me the excuse to return to the surf hut and do the same. By the time we meet at her car to collect the rest of her gear, I have composed myself enough to ensure I don’t make an absolute tit of myself.

Half an hour later, we are sitting back at our tents, with a cup of tea and two large slices of Madeira cake. She has taken off her wetsuit, and is now dressed in shorts, a loose cotton shirt and a bikini top that is low cut enough to give a good view of her breasts. I look away quickly, hoping she hasn’t noticed me ogle them, though her arch smile suggests I haven’t been as discreet as I’d wished. I resolve to rein it in. I need to take this easy if I’m to have any success

‘So what now?’ I say as I finish the last gulp of tea.

‘Fancy a swim?’

‘Always wait at least half an hour in case of cramp.’

‘Says who?’

‘My mother,’ I say, laughing ‘Fuck knows if it’s true. It’s just what she always said. Which reminds me. ‘I suppose I’d better call her …’

‘… but you don’t know what to say?’

‘Nope. How about you?’

‘My parents died a long time ago.’

‘Sorry.’

‘Don’t be. Are you close to your mum?’

‘Not especially. She lives in Poland now. She’s a bit of a recluse.’ To be honest, I don’t know if she’ll even have seen the news. It’s been at least six weeks since we’ve spoken, so how can I ring her now and tell her I’m going to die tomorrow? I could add that our relationship, always a tricky one, had got worse after Karo’s death, but that’s way too intimate for someone I’ve just met. I take a different tack.

‘What do mums know anyway? Let’s risk cramp.’

The wind has died down, but the current is still strong. Without our wetsuits the water is gaspingly cold, though once we start moving around we soon warm up. We race each other across the bay, dive and tumble, splash and jump the waves as if we are ten years old. It is exhilarating till the exertion of the surfing catches up with us and we decide, simultaneously, to head back to our camp. We dry ourselves off before flopping onto the towels. Poppy starts spraying suntan lotion.

‘Do my back and shoulders, will you?’ she says sitting up. Her skin is soft to the touch; I rub the lotion quickly and pull on a shirt before she can return the favour. I dive back on the towel and pick up my book; the last thing I need now is an embarrassing arousal. Particularly when she is lying so close to me. I wish I could reach out and touch her, confident that she’d respond in kind but she has given no indication that such advances would be welcome and I don’t want to push my luck. I force myself to focus on the page.

Soon, my eyes are crossing and before long I am asleep. I am walking in a forest with Karo and Mum, who is a few yards ahead of us. Karo and I are getting tired, we ask Mum to slow down, but she quickens her pace. Mum, we cry, slow Down, Wait for us. She doesn’t seem to hear us, and so we raise our voices louder. She stops this time, turns round and looks at us. But Karo, Yan, you can’t follow me. You’re dead. Why didn’t you tell me you were going to die? I wake with a start. My eyes are full of tears, and to my embarrassment I have dribbled on the towel. I can hear voices above my head. I wipe my eyes and mouth discreetly and sit up. We have a visitor, a white woman in her sixties, who is sitting beside Poppy, talking quietly.

‘This is Margaret,’ says Poppy. ‘She was in her car, but she needed some fresh air. Margaret, meet Yan.’

‘I’m not sure if it’s sensible,’ Margaret’s voice is shaking, ‘I should be on the road, really, but the traffic …’ I exchange a glance with Poppy, not sure whether I should feel glad or sad to be proved right. Margaret takes a deep breath and carries on, ‘It was so hot and there were so many cars – I just had to get out …’

‘Looks like you need to rest for a bit,’ says Poppy. ‘Why not stop and have a drink, then check traffic in a while. If things are better, you can get going, but if not, you can stay as long as you like.’

I know it is churlish, Poppy is right to be so sympathetic and, after all, this is what she promised she would do. Still, I can’t help resenting this stranger interrupting our little idyll. I am not sure I want to share her with anyone.

‘This is so kind of you.’ Margaret accepts a proffered cup of tea.

‘Don’t mention it,’ says Poppy. ‘The more the merrier, wouldn’t you say Yan?’

‘Of course.’ I am forced into my very best polite smile. I even let her know she can use the surf club if she needs to recharge her phone. But, although I take the tea Poppy offers, and join them on the chairs, I don’t join in the conversation; I pretend to read my book instead. It’s not Margaret’s fault – she seems pleasant enough - it’s just that she’s shattered the intimacy Poppy and I have been building up. And now there are three of us, the atmosphere isn’t quite the same. .

I can see it is going to be a very long night.

Margaret

I am in the middle of ironing when I hear the news. I’m still trying to work out what I think about the end of a play that I’ve just heard and at first I’m not really paying attention. It is only the mention of La Palma that makes me take notice. All at once, I am back in that horrible room sifting through paper after paper, trying to make rational decisions about which organisations to save and which to cut. Every decision was a bad one, but at the time some options were more palatable than others. La Palma was one of many such arguments. David tried to persuade us we needed the early warning unit because one day something bad would happen. He used the example of Cumbre Vieja to illustrate his point, providing graphic detail of how monitoring seismic activity could prepare us for its possible collapse enabling us to evacuate. His projections even identified Cornwall as a high risk area.But Andrew was equally persuasive the other way,arguing that we couldn’t afford the luxury of spending money worrying about things that might never come to pass. Now it seems that that David was right: the decision we made was the worst of all and I am caught in the middle of it. Shocked, I drop the iron on my favourite shirt. It sizzles, marking the material with a permanent burn as I pull it away. I curse and then it occurs to me that a ruined shirt might be the least of my worries.

The funny thing is that, once I’ve convinced myself that the choice we made eight years ago has nothing to do with what is happening now, my first thought isn’t escape, or whether I might drown. It isn’t even Hellie. My first thought is that I should ring Kath. Ring Kath? That’s a joke. We haven’t spoken for years. She’d hardly appreciate a phone call from me now and where would I start? I switch the iron off, put the shirt to one side and sit down by the window, considering my options. The sun is high in the sky, its beams glinting on the blue water in the bay in front of me. It doesn’t seem possible that this time tomorrow it will be gone. I stand there for far too long,

pondering what to do: a balance between driving long distance with my dodgy knees or scrambling for a place on the train. Even getting to the station will take some effort. Hellie always said I’d regret living this far out of town but up until now I’ve always told her she worries too much, citing the freedom of walking into open countryside from my front door. Today, for the first time I have to admit maybe she was right.

Hellie … Thinking of Hellie makes up my mind. I have to get to her as quickly as I can, and judging by the pictures on my TV screen I’ll have no chance of making my way through the crowds at the station. Knees or no knees it looks like the car is my only option. I send her a reassuring text and begin to get ready to leave. Despite the urgency, once I’ve made the decision, I just cannot make myself hurry. A sense of disbelief washes over me. I still can’t quite take in the thought that I am leaving my home for good, that by this time tomorrow the house will be gone and with it all the possessions I can’t take with me. I find myself paralysed with indecision about what to take and what leave behind. Some things are obvious: Grandma’s recipe book, my wedding photos and Hellie’s baby pictures. Others less so. I want to bring the painting of Venice that hangs in the living room. Richard and I bought it on honeymoon – it’s had pride of place in all our houses since – but it’s heavy and takes up a lot of space. I’d love to keep the family Bible. It’s been with us since 1842, with every generation meticulously recorded since then. With regret, I decide to leave it: it is just too bulky. I spend far too long trying to choose what stays and what comes with me. In the end, I store the Bible, the painting and a couple of other precious items in a cupboard upstairs, wrapped in plastic, in the vain hope that this will protect them from the sea. It seems criminal to leave such things behind, but I just can’t manage them. It’s going to be hard enough that I’m going to have to camp in Hellie’s tiny flat for a while without me filling it with clutter. So, in addition to the personal items, I just take a couple of suitcases of clothes, a handful of my favourite novels, and a few CDs.

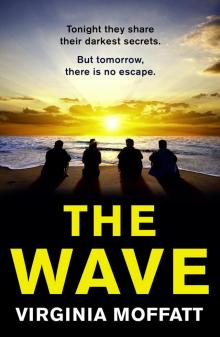

The Wave

The Wave